Digital and analogue recordings as repository of memory and vehicles of interjection

Paper presentation, Post-Autonomia conference, SMART Project Space, University of Amsterdam,

By M.Karagianni & V.Semou, Amsterdam 2011

——————————————————————–

ABSTRACT: In this paper we argue for an art practice that is autonomous in terms of its mode of production and we examine the re-enactment and appropriation of recordings as one of the artistic methods of resistance.

Our case studies refer to the practice of 2 artistic-political collectives: the Mountain Theatre in Greek resistance to nazis occupation in the 40’s, and the contemporary art collective BLW in California. In the former case, guerilla fighters took part as amateur actors, the appointed time schedule of each performance was adjusted so that most people could join, while the play was adapted to illustrate personas found in the villages for integrating a revolutionary message within everyday life. In the latter, the collective involves the memorization of significant recordings in the history of radical media speeches by inviting audience members to publicly re-enact them. Through this practice, the artists recover the power of speech in a culture where oral competence is displaced by media forms.

Inspired from the above mentioned practices, our discussion in the paper shifts to our own practice and experience as artists within the contemporary milieu of activism in the Netherlands. Digital and analogue recordings of previous actions join the live broadcasting of the voices and demands at protests that address social problems, such as housing shortage and budget cuts. Unlike the saturation of media archives that stay inactive for passive viewing/ listening, the re-use of our recorded material and live stream during protests show the continuation of the struggle that can result in the empowerment of peoples’ engagement.

——————————————————————————–

Introduction

Since the institutionalization of the avant-guard, art has become autonomous from reality. Art galleries and events are populated mostly with artists, art critics and intellectuals. If art’s role in the welfare social state was to interweave with and change the social structures then where is the diverse public that art should address to? The question of how to mingle art with everyday life must be always under re-configuration.

Subsiding infrastructure and art institutes has provided enclaves for artists to experiment and contribute to knowledge and innovation. But what is happening with this knowledge when it becomes the institution’s product and its access falls under copyright restrictions? If the value of the research/project is not returned to public good and public funding is spent to monopolized corporate services, from Apple’s gadget, Microsoft operating systems, Facebook artists portfolios, how this system can sustain itself?

In this paper we investigate two cases of cultural activism outside institutions and unbound to monetary value; the Mountain Theatre in Greek resistance during the occupation of the nazis in early 40’s, and the contemporary art collective BLW in California. Inspired from their practices, our discussion in the paper will shift to our own practice and experience as artists within the contemporary milieu of activism in the Netherlands.

Mountain theatre – Greece 1944

In the case of Mountain theatre, performance was put forward as a means of both individual and collective liberation. Mountain theatre was consisting of few companies that were touring in the north of Greece. Among them, “Laiki Skini” was solely a guerilla theatre which throughout the course of performances preserved the disposition of a militant theatre since it never presented its work in a more traditional setting of artistic venues such as festivals or conventional theatre spaces.

The creation of the artistic department of EAM in the summer of 1944 signalised the beginning of the regular tour of Laiki Skini under the flag of the VIII Division of ELAS. Poet and philologue Kotzioulas would be both its Director and Director of the Artistic Department (Myrsiades, 32). The Division’s confidence in the troupe, allowed a considerable degree of independence of the troupe, although it was not to remain completely autonomous; according to Kotzioulas; that is, it was considered semi-military unit [even without the fully support of the National Liberation Front of Greece(EAM)].

“Setting off, troupe members were assigned weapons to defend themselves on the road. So that they would further uphold the honour of the Division they were passed in special formation before the Captain who impressed upon them the importance of “not committing any improprieties on the road” (Myrsiades, 32).

When the troupe first started touring in the north-east mountains of Greece, it encountered the perception of theatre in people’s mind outside the capital of Greece; that was mostly a medium of staged mimicry and caricature performance. However, this changed with the establishment of Laiki Skini as a recognised and valuable artistic experience. The creative persons in the villages would contribute in the texts and the performance of the plays. Fighters would impersonate people of the villages in staged re-enactments of historical events of the revolutionary past of Greece. Their participation in the plays was a means to keep the memory of their involvement in the resistance alive. The troupe would adjust the schedule of performances so that more people could join. The stage would be done ad-hoc with stones, wood and whatever was available in the villages. Tickets would be the accommodation and alimentation of the troupe. These practices were what gave the opportunity to the theatre to integrate art in such small communities under conditions of poverty and lack of aesthetic knowledge and experience. In this direction, the troupe took a radical stance and it did away with more highly aesthetic texts in order to stimulate from below and within the available means the spirit of liberation and creativity to the indigenous population. Accordingly, the director, Kotzioulas, would combine parts of existing plays he would watch at theatre festivals, simplifying them and enriching them with personal stories he would encounter in the villages.

When the troupe first started touring in the north-east mountains of Greece, it encountered the perception of theatre in people’s mind outside the capital of Greece; that was mostly a medium of staged mimicry and caricature performance. However, this changed with the establishment of Laiki Skini as a recognised and valuable artistic experience. The creative persons in the villages would contribute in the texts and the performance of the plays. Fighters would impersonate people of the villages in staged re-enactments of historical events of the revolutionary past of Greece. Their participation in the plays was a means to keep the memory of their involvement in the resistance alive. The troupe would adjust the schedule of performances so that more people could join. The stage would be done ad-hoc with stones, wood and whatever was available in the villages. Tickets would be the accommodation and alimentation of the troupe. These practices were what gave the opportunity to the theatre to integrate art in such small communities under conditions of poverty and lack of aesthetic knowledge and experience. In this direction, the troupe took a radical stance and it did away with more highly aesthetic texts in order to stimulate from below and within the available means the spirit of liberation and creativity to the indigenous population. Accordingly, the director, Kotzioulas, would combine parts of existing plays he would watch at theatre festivals, simplifying them and enriching them with personal stories he would encounter in the villages.

These stories are what in other words Guattari refers to as the “trivia”.

“What I call militant representation is itself simply the manifestation of unconscious signifiers, potential utterances and creative crises relating to substances as yet insignificant, and producing subjective effects simultaneously affecting the whole of the historical sequence under consideration [..] such statements will no doubt be deprecated as reducing historical causality to trivia, and in a sense this is quite true.

To what extent are the masses of people prepared to sacrifice themselves for things that ‘really matter’, to shoulder their fundamental historical tasks? Under what conditions would they consider uniting as one man to form a vast war machine like the one that swept all before 1917? Surely the first condition should be an assurance that the trivia that are for them the salt of life, the source of their desire, would not be forgotten in the process?” (Guattari, 194 )

Guattari calls the manifestation of such collective utterances expressed by a subject (militant revolutionary groups), a “militant representation” which however contingent might be, it is crucial to revolutionary breakthroughs and supports the extension of time in history. The significance of such utterances enhances people’s imaginary outside the control of the parties’ apparatus that is put forward in every situation (Guattari, 194-195).

In our artistic practice, we are exploring how to provide ground that stimulates such collective utterances. And we’re exploring how the ‘record’ can contribute to a kind of shared re-call, namely to the construction and activation of collective memory. Experimenting with the relationships of collective memory and collective action, we suggest, among other things, the activation of historical or personal archives by playing them back and more specifically by re-speakingthem.

BLW collective – California currently

We are inspired by BLW, an artist-activist collective which is engaged in recovering the power of speech in culture where oral competence is displaced by media forms. In this direction so far they have publicly recited significant recordings in the history of radical media. More specifically, using recorded archives and other forms of documentation they have invited the audience to read, re-speak or even re-stage speeches and interviews of activists.

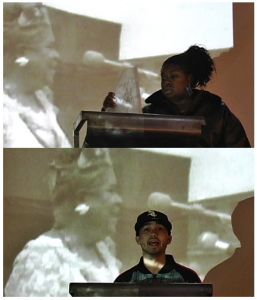

As an example of their practice, we could present here their recitations of a speech by the civil rights activist Queen Mother Moore. Here below is a video excerpt of this re-speaking in Chicago. It was in the frames of Pilot TV, a workshop for radical media. From a stage, the collective addressed a modest group of artists and activists, gathered to experiment with the possibilities of radical media today.

The same speech was re-enacted in a performance workshop (in collaboration with City Studio Youth Art Education Project in San Francisco) where students re-spoke Queen Mother Moore ‘s speech, as part of their investigation of the Prison Industrial Complex.

In our work we try to incorporate practices such as those of BLW and Laiki Skini. Driven from our desire to actively participate in the contemporary public discourses, we proceeded in the construction of a mobile platformby hijacking two shopping carts. We incorporated in the construction both digital and analogue media: a megaphone, a microphone, a pc for recording-replaying recordings, ad-hoc internet connection, live broadcasting, a pinboard, pickets, FM transmission, a printer, a website, a blackboard. In action, this platform becomes the stage for making public: opinions, stories, information. It collects them and distributes them back. It creates a kind of street blogging, propagating our messages or the messages of the people whose cause we support. In demonstrations, in public events, in public spaces, on the internet.

So far, half of our customised platform participated in two demonstrations: The first was the protest for social housing against the budget cuts imposed by the new Dutch government and against the housing shortage, organised by SASH. The second was the protest organised by a resident’s collective against the housing speculation of the owner of the housing complex they were living in Platanenweg.

To give an example of how we gave content in the platform, we asked friends to translate into their own language and speak the demands which SASH put on the agenda calling for affordable housing for everyone. We recorded their speeches and played them while marching in the second demonstration organised by the residents of Platanenweg. In this way, the demands from the first demonstration joined and strengthened the protesters’ voices of the second. Hence, the material we record forms an archive that stays active and plays a significant role to every future action.

In BLW ‘s work, we saw the significance of taking the position of a speaker. In this light, it is also significant for us to ask people to speak because it exposes and reveals a part of oneself. This exposure can be liberating and/or painful. Next to it, we take into account other forms of publicizing one’s point of view e.g writing and printing, since one has to feel welcome to do so. It might be an act of sharing ideas; resonating existing ones; an act of belonging; of becoming a member of a collective.

Having this last standpoint in mind, in our project, we aspire to join our voices together with the voices of protesters and with the voices of the near and distant past. All these voices mingle to create a sense of belonging to one struggle and each one of them is resonated by its repetition and in the words of others.

Under this perspective, Laiki Skini resonates an oral narration of memory, which is not based on the recording devices. Theatrical plays were based on these narrations of the residents of the villages combined with adapted historical texts. The significance of these texts was such that in order to be performed outside guerilla theatre, they had to be reproduced by hand.

Today the possibilities of recording and the expansion of their use contribute to a repository of history far more expansive and diverse. At the same time they function as technologies of forgetting, since we get re-assured by their infinite accumulative capacity and we abandon our own effort to remember together with other ways of exercising our memory. However, how this moment can survive in the future depends also on what will become of the record; and on how it can participate in structures of archive, access and distribution.

The recitation of a recorded speech or the performances of Laiki skini without the aid of any recording devices than writing, are an act of committing them to memory. Their re-speaking embodies the history of radical politics. The re-playing of recordings and the re-enacting of radical actions and events, connects history to the present by juxtaposing political demands of the past and of the present. It interrogates our own position as subjects of today in relation to ideas, experiences and political/social practices of the past. Moreover, this re-playing instil the current moment with the spirit of resistance and possibility; but, at the same time, it gives us a bitter feeling of the vicious circle of unsolved issues from previous struggles to now.

Conclusion

A pertinent question remains; among all those voices and all these stories that surrounds us, which ones should be told and re-told in order to assist acts of empowerment?

In this investigation we started digging in the archives of the institute of social History in Amsterdam and in collectively defined online platforms such as indymedia. But also,we dig in our own past and current experience of social struggle, as well as in those of friends and acquaintances. Found sound recordings such as from may 68, from the occupation of the polytechnic school of Athens 73, or personal witnesses about police brutality, are placed next to those created in protests at the disposal of anyone who would wish to visit, revisit and re-activate them.

In this investigation we started digging in the archives of the institute of social History in Amsterdam and in collectively defined online platforms such as indymedia. But also,we dig in our own past and current experience of social struggle, as well as in those of friends and acquaintances. Found sound recordings such as from may 68, from the occupation of the polytechnic school of Athens 73, or personal witnesses about police brutality, are placed next to those created in protests at the disposal of anyone who would wish to visit, revisit and re-activate them.

“The idea of autonomy brings us quickly to the idea of dependency; paradoxically dependency is a condition of autonomy.” (Pierce, 26)

We need many voices to change our life. Protests out in the streets is still one of a great value strategy against neoliberal reform. Isolated struggles of groups, such as the ones of the cultural sector, the postmen, the cleaners, the students, will not bring a desired utterance of resistance. There is the urgency for a general strike and an open call for workers, unemployed and sans-papiers, pensioners, domestic labourers and all those affected by the budget cuts and the neo-liberal agenda to join their forces to one struggle. We can’t all claim to be in the same position in relation to power and designations of authority, but speaking with each other, being dependent on each other’s struggle, is a way to understand these structures, and the ways we are all implicated in the various stratums of power and powerlessness. What different groups, collectives and collaborations ought to be autonomous from, are relations of dominance reproduced in the unions, parties, and centralised organizations, whose bureaucratic procedures deactivate people’s utterances.

“This is the practise of ‘politics in the first person’: a realisation that the future starts now, that a collective practice in the factory must be matched at home.” (AutonomiaOperaia, libcom.org)

If cultural workers ought to support a continual reconfiguration of standpoints and actions in order to shift relationships and roles in society, they should take their creative practice outside to the streets, to grassroots activist political groups, to social collectives of minorities, to individual activists and not just using those groups for the creation of any so called “social” art. For example, why the cultural sector has to do its own campaign against the budget cuts of the dutch government, if it is art that should shake the norms and give space for alternative thought within the social interactions of society?

“Artist’s role is not anymore in the fore-front of the engine of social change, but rather to be an activator in global and local networks of communication. Being in the contemporary, rather than producing a belated or elevated response to everyday.” (Papastergiadis, 466-469)

Collaboration is urgent. Protesting together and addressing art to non privileged population is one method. Reconstruction /reactivation of the radical past in the present with the help of media to empower collective awareness is another. We have to employ all the means we got because choosing is a luxury we cannot afford.

References

BLW, Information retrieved on february 2011 by the websites:

http://www.carbonfarm.us/blw/blwpages/home.html,

http://citystudio-pic.blogspot.de/2008/03/saturday-performance-workshop-with-blw.html

Guattari, Félix. Molecular Revolution, “Casuality, Subjectivity and History”, 1984

Myrsiades, Linda. “Narrative, Theory, and Practice in Greek Resistance Theatre”, Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora, 9-83.

Papastergiadis, Nikos. “Modernism and Contemporary Art”. Theory Culture Society 23, [2006]: 466-469.

Pierce, Sarah. “Murmurs and Legacies”, Frameworks, Autonomy Project, Onomatopee 43.1, [2010]: 26-27.

“Politics in the First Person: the autonomous workers movement in Italy – Wicked Messengers” Article about Autonomia Operaia and the radical workers’ movement in Italy in the 1960s and 70s. Retrieved on february 2011 by the website: http://libcom.org/library/politics-first-person-autonomous-workers-movement-italy-wicked-messengers